Like medical coding, medical billing might seem large and complicated, but it’s actually a process that’s comprised of eight simple steps.

These steps include: Registration, establishment of financial responsibility for the visit, patient check-in and check-out, checking for coding and billing compliance, preparing and transmitting claims, monitoring payer adjudication, generating patient statements or bills, and assigning patient payments and arranging collections.

Bear in mind that there is a difference between “front-of-house” and “back-of-house” duties when it comes to medical billing.

Register Patients

When a patient calls to set up an appointment with a healthcare provider, they effectively preregister for their doctor’s visit. If the patient has seen the provider before, their information is on file with the provider, and the patient need only explain the reason for their visit. If the patient is new, that person must provide personal and insurance information to the provider to ensure that that they are eligible to receive services from the provider.

Confirm Financial Responsibility

Financial responsibility describes who owes what for a particular doctor’s visit. Once the biller has the pertinent info from the patient, that biller can then determine which services are covered under the patient’s insurance plan.

Insurance coverage differs dramatically between companies, individuals, and plans, so the biller must check each patient’s coverage in order to assign the bill correctly. Certain insurance plans do not cover certain services or prescription medications. If the patient’s insurance does not cover the procedure or service to be rendered, the biller must make the patient aware that they will cover the entirety of the bill.

Patient Check-in and Check-out

Patient check-in and check-out are relatively straight-forward front-of-house procedures. When the patient arrives, they will be asked to complete some forms (if it is their first time visiting the provider), or confirm the information the doctor has on file (if it’s not the first time the patient has seen the provider). The patient will also be required to provide some sort of official identification, like a driver’s license or passport, in addition to a valid insurance card.

The provider’s office will also collect copayments during patient check-in or check-out. Copayments are always collected at the point of service, but it’s up to the provider to determine whether the patient pays the copay before or immediately after their visit.

Once the patient checks out, the medical report from that patient’s visit is sent to the medical coder, who abstracts and translates the information in the report into accurate, useable medical code. This report, which also includes demographic information on the patient and information about the patient’s medical history, is called the “superbill.”

The superbill contains all of the necessary information about medical service provided. This includes the name of the provider, the name of the physician, the name of the patient, the procedures performed, the codes for the diagnosis and procedure, and other pertinent medical information. This information is vital in the creation of the claim.

Once complete, the superbill is then transferred, typically through a software program, to the medical biller.

Prepare Claims/Check Compliance

The medical biller takes the superbill from the medical coder and puts it either into a paper claim form, or into the proper practice management or billing software. Biller’s will also include the cost of the procedures in the claim. They won’t send the full cost to the payer, but rather the amount they expect the payer to pay, as laid out in the payer’s contract with the patient and the provider.

Once the biller has created the medical claim, he or she is responsible for ensuring that the claim meets the standards of compliance, both for coding and format.

The accuracy of the coding process is generally left up to the coder, but the biller does review the codes to ensure that the procedures coded are billable. Whether a procedure is billable depends on the patient’s insurance plan and the regulations laid out by the payer.

While claims may vary in format, they typically have the same basic information. Each claim contains the patient information (their demographic info and medical history) and the procedures performed (in CPT or HCPCS codes). Each of these procedures is paired with a diagnosis code (an ICD code) that demonstrates the medical necessity. The price for these procedures is listed as well. Claims also have information about the provider, listed via a National Provider Index (NPI) number. Some claims will also include a Place of Service code, which details what type of facility the medical services were performed in.

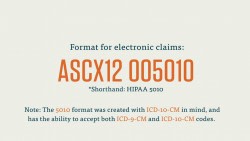

Billers must also ensure that the bill meets the standards of billing compliance. Billers typically must follow guidelines laid out by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Office of the Inspector General (OIG). OIG compliance standards are relatively straightforward, but lengthy, and for reasons of space and efficiency, we won’t cover them in any great depth here.

Transmit Claims

Since the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), all health entities covered by HIPAA have been required to submit their claims electronically, except in certain circumstances. Most providers, clearinghouses, and payers are covered by HIPAA.

Note that HIPAA does not require physicians to conduct all transactions electronically. Only those standard transactions listed under HIPAA guidelines must be completed electronically. Claims are one such standard transaction.

Billers may still use manual claims, but this practice has significant drawbacks. Manual claims have a high rate of errors, low levels of efficiency, and take a long time to get from providers to payers. Billing electronically saves time, effort, and money, and significantly reduces human or administrative error in the billing process.

In the case of high-volume third-party payers, like Medicare or Medicaid, billers can submit the claim directly to the payer. If, however, a biller is not submitting a claim directly to these large payers, they will most likely go through a clearinghouse.

A clearinghouse is a third-party organization or company that receives and reformats claims from billers and then transmits them to payers. Some payers require claims to be submitted in very specific forms. Clearinghouses ease the burden of medical billers by taking the information necessary to create a claim and then placing it in the appropriate form. Think of it this way: A practice may send out ten claims to ten different insurance payers, each with their own set of guidelines for claim submission. Instead of having to format each claim specifically, a biller can simply send the relevant information to a clearinghouse, which will then handle the burden of reformatting those ten different claims.

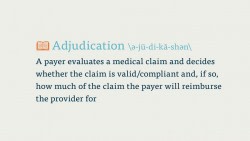

Monitor Adjudication

Once a claim reaches a payer, it undergoes a process called adjudication. In adjudication, a payer evaluates a medical claim and decides whether the claim is valid/compliant and, if so, how much of the claim the payer will reimburse the provider for. It’s at this stage that a claim may be accepted, denied, or rejected.

A quick word about these terms. An accepted claim is, obviously, one that has been found valid by the payer. Accepted does not necessarily mean that the payer will pay the entirety of the bill. Rather, they will process the claim within the rules of the arrangement they have with their subscriber (the patient).

A rejected claim is one that the payer has found some error with. If a claim is missing important patient information, or if there is a miscoded procedure or diagnosis, the claim will be rejected, and will be returned to the provider/biller. In the case of rejected claims, the biller may correct the claim and resubmit it.

A denied claim is one that the payer refuses to process payment for the medical services rendered. This may occur when a provider bills for a procedure that is not included in a patient’s insurance coverage. This might include a procedure for a pre-existing condition (if the insurance plan does not cover such a procedure).

Once the payer adjudication is complete, the payer will send a report to the provider/biller, detailing what and how much of the claim they are willing to pay and why. This report will list the procedures the payer will cover and the amount payer has assigned for each procedure. This often differs from the fees listed in the initial claim. The payer usually has a contract with the provider that stipulates the fees and reimbursement rates for a number of procedures. The report will also provide explanations as to why certain procedures will not be covered by the payer.

(If the patient has secondary insurance, the biller takes the amount left over after the primary insurance returns the approved claim and sends it to the patient’s secondary insurance).

The biller reviews this report in order to make sure all procedures listed on the initial claim are accounted for in the report. They will also check to make sure the codes listed on the payer’s report match those of the initial claim. Finally, the biller will check to make sure the fees in the report are accurate with regard to the contract between the payer and the provider.

If there are any discrepancies, the biller/provider will enter into an appeal process with the payer. This process is complicated and depends on rules that are specific to payers and to the states in which a provider is located. Effectively, a claims appeal is the process by which a provider attempts to secure the proper reimbursement for their services. This can be a long and arduous process, which is why it’s imperative that billers create accurate, “clean” claims on the first go.

Generate patient statements

Once the biller has received the report from the payer, it’s time to make the statement for the patient. The statement is the bill for the procedure or procedures the patient received from the provider. Once the payer has agreed to pay the provider for a portion of the services on the claim, the remaining amount is passed to the patient.

In certain cases, a biller may include an Explanation of Benefits (EOB) with the statement. An EOB describes what benefits, and therefore what kind of coverage, a patient receives under their plan. EOBs can be useful in explaining to patients why certain procedures were covered while others were not.

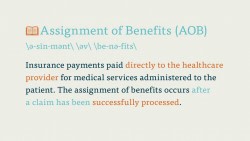

Follow up on patient payments and handle collections

The final phase of the billing process is ensuring those bills get, well, paid. Billers are in charge of mailing out timely, accurate medical bills, and then following up with patients whose bills are delinquent. Once a bill is paid, that information is stored with the patient’s file.

If the patient is delinquent in their payment, or if they do not pay the full amount, it is the responsibility of the biller to ensure that the provider is properly reimbursed for their services. This may involve contacting the patient directly, sending follow-up bills, or, in worst-case scenarios, enlisting a collection agency.

Each provider has it’s own set of guidelines and timelines when it comes to bill payment, notifications, and collections, so you’ll have to refer to the provider’s billing standards before engaging in these activities.